Imagine living or working near an industrial facility in Vernon, Los Angeles, where an invisible, odorless chemical seeps into the air, silently raising your risk of cancer with every breath. This chemical, ethylene oxide (EtO), is vital for sterilizing medical devices but deadly as a known human carcinogen. Despite overwhelming scientific evidence of its dangers, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) has left its safety standards untouched since 1984, exposing workers and nearby residents to preventable harm. In neighborhoods already burdened by pollution, this regulatory inaction feels like a betrayal of public trust. Why has OSHA failed to act when the stakes are so high? This glaring oversight demands exploration, as it reveals not just a failure of policy but a deeper systemic issue affecting vulnerable communities across the nation. The reasons behind this delay, the risks it perpetuates, and the urgent need for change form the heart of this pressing discussion.

Unmasking a Hidden Threat

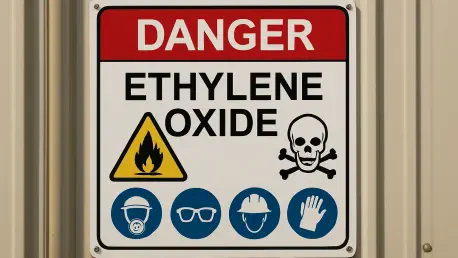

Deep in the industrial zones of Los Angeles, a silent danger lurks in the form of ethylene oxide, a chemical essential for sterilizing roughly half of all medical devices used in the United States. Its importance to healthcare is undeniable, ensuring that tools critical for surgeries and treatments remain safe for patients. However, the darker side of EtO emerges with prolonged exposure, which has been conclusively linked to severe health issues like breast cancer, leukemia, lymphoma, and even respiratory distress. Both the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) have sounded alarms about these risks, painting a grim picture for those who work in or live near sterilization facilities. Day after day, unsuspecting workers and residents breathe in this toxic substance, often without any awareness of the invisible threat that surrounds them. This reality raises a critical question: how can a chemical so vital to public health also be allowed to endanger so many lives with such impunity?

Beyond its immediate health impacts, the pervasive use of EtO reveals a troubling gap in how society balances necessity with safety. While hospitals rely on sterilized equipment to save lives, the very process of sterilization can jeopardize the well-being of entire communities, particularly in areas like Vernon where industrial activity is concentrated. Workers in these plants face the highest exposure levels, often without adequate protective measures or even basic knowledge of the risks they encounter daily. Meanwhile, families living in the shadow of facilities like Sterigenics absorb the same carcinogen through the air, compounding their vulnerability in neighborhoods already struggling with other environmental burdens. This dual reality—where a lifesaving tool becomes a life-threatening hazard—underscores the urgent need for updated regulations that reflect the true scope of EtO’s dangers. Until that happens, countless individuals remain caught in a cycle of risk that could, and should, be mitigated.

Stalled at the Federal Level

At the core of this public health crisis lies OSHA’s startling inaction on EtO safety standards, a failure that stretches back nearly four decades. The current permissible exposure limit (PEL) for EtO stands at 1 part per million (ppm), a threshold established in 1984 when scientific understanding of the chemical’s toxicity was far less advanced. Today, research reveals EtO to be up to 60 times more carcinogenic than previously believed, a finding that should have triggered immediate regulatory updates. The EPA has proposed a safer limit of 0.1 ppm, acknowledging the heightened danger, but even this adjustment won’t take effect until a decade from now in 2035. OSHA, however, remains silent, clinging to an outdated standard that exposes workers to levels ten times higher than what experts now deem acceptable. This regulatory stagnation isn’t just a bureaucratic oversight; it’s a profound ethical lapse that prioritizes inaction over the protection of human lives.

Delving deeper into this delay, it becomes evident that OSHA’s failure reflects broader systemic challenges within federal oversight. Updating safety standards requires navigating a complex web of industry pushback, political priorities, and resource constraints, often leaving agencies like OSHA paralyzed despite clear evidence of harm. While scientific advancements have outpaced policy, workers continue to face preventable risks in environments where EtO is handled daily. The consequences of this lag are not abstract—they manifest in rising health issues among those most exposed, from plant operators to neighboring residents. Moreover, the disconnect between OSHA’s current limits and the EPA’s proposed reductions highlights a lack of coordination among federal bodies tasked with safeguarding public health. Until these agencies align their efforts and act decisively, vulnerable populations will remain caught in the crosshairs of a regulatory void that could have been filled years ago with the right political will.

Bearing the Burden of Inequality

In Los Angeles, the dangers of EtO exposure are not evenly distributed, with industrial neighborhoods like Boyle Heights, Maywood, and Huntington Park bearing a disproportionate share of the burden. These communities, often home to lower-income and marginalized residents, are already steeped in environmental challenges, from smog to industrial waste. The presence of facilities like Sterigenics in Vernon adds another layer of risk, emitting EtO into the surrounding air and amplifying health threats for those who can least afford to escape them. This stark environmental inequality lays bare a troubling truth: pollution and its consequences often fall heaviest on those with the fewest resources to fight back. Local efforts to address emissions, such as violations issued by the South Coast Air Quality Management District, have flagged problems, yet these bodies lack the authority to enforce workplace safety standards—a responsibility that rests squarely with OSHA.

Compounding this injustice is the historical pattern of neglect that has left such communities vulnerable to industrial hazards. For decades, industrial zones have been placed in areas where residents have little political clout to demand change, creating a cycle of exposure and illness that feels almost inevitable. In Vernon, for instance, the proximity of homes and schools to sterilization plants means that entire families breathe in carcinogenic air, often without access to adequate healthcare to address the resulting conditions. While local advocacy groups have raised alarms, their calls for stricter controls are hampered by the limits of regional authority, leaving federal inaction as the true barrier to progress. This situation demands more than patchwork solutions; it requires a fundamental rethinking of how safety regulations are prioritized to protect the most at-risk populations. Until that shift occurs, environmental inequality will continue to exacerbate the human toll of EtO exposure in Los Angeles and beyond.

Echoes of a Wider Problem

The crisis of EtO exposure extends far beyond the borders of California, revealing a national pattern of risk near sterilization facilities across the country. In places like Willowbrook, Illinois, and Laredo, Texas, elevated cancer rates have been documented in communities surrounding these plants, with exposure levels often exceeding federal safety thresholds by alarming margins. These cases mirror the situation in Los Angeles, where the health of entire neighborhoods is compromised by a chemical essential to medical care yet deadly in its unintended reach. Shockingly, many facilities remain in compliance with outdated regulations, exploiting loopholes that prioritize operational ease over public well-being. Even more troubling, several plants, including three in California, have secured exemptions from the Clean Air Act, allowing them to sidestep stricter emission controls while communities suffer the consequences.

This widespread issue underscores a systemic failure to address the true scope of EtO’s impact, as federal oversight lags behind the reality on the ground. Each affected area tells a similar story: workers and residents face heightened health risks while regulatory bodies fail to enforce standards that reflect current scientific knowledge. The exemptions granted to certain facilities only deepen the sense of injustice, signaling that corporate interests often outweigh the needs of vulnerable populations. In the absence of updated federal mandates, states and local governments are left to grapple with a problem they lack the full authority to solve. This patchwork approach results in uneven protections, leaving some communities more exposed than others based purely on geography or political will. Until a cohesive national strategy emerges, the echoes of this crisis will continue to reverberate in towns and cities far beyond the industrial heart of Los Angeles.

Pushing for Change Now

Amid the disheartening reality of federal inaction, there lies a clear path forward through actionable solutions that could mitigate the risks of EtO exposure. Technologies such as continuous air monitoring, state-of-the-art ventilation systems, and advanced leak detection are already available, offering practical ways to reduce exposure in workplaces and surrounding areas. Routine medical screenings for workers could catch health issues early, providing a lifeline for those on the frontlines of this crisis. Yet, despite the existence of these proven tools, their implementation remains stalled by a lack of political resolve at both federal and state levels. California, with its history of environmental leadership, stands poised to set an example by adopting stricter workplace protections and pushing for community-focused safety measures. The opportunity for change is ripe; it simply awaits the courage to act.

Furthermore, the role of local action cannot be overstated in bridging the gap left by federal delays. Los Angeles has the chance to become a beacon of environmental and labor justice by advocating for policies that prioritize human health over industrial convenience. Community mobilization, paired with partnerships between local governments and advocacy groups, could drive the adoption of modern safety protocols that protect both workers and residents. Historical examples of successful activism in the region offer a blueprint for how collective action can force accountability, even when higher authorities falter. While the technology and research needed to address EtO risks are ready, the missing piece remains the commitment to turn plans into reality. Looking back, it’s evident that past efforts to combat pollution in California yielded results when leaders listened to affected communities—now, that same spirit of resolve must guide the fight for safer standards in the face of this ongoing public health threat.