Today we’re joined by Sofia Khaira, a distinguished specialist in diversity, equity, and inclusion. With a deep focus on enhancing talent management, Sofia helps organizations cultivate truly inclusive environments. We’ll be exploring the delicate balance of workplace communication policies following a recent tribunal case where an employee was awarded nearly £11,000 after being told not to speak his native language. Our discussion will cover how managers should respond to language-based complaints, the critical failures that can undermine internal investigations, and the essential steps for creating equitable policies and training culturally competent leaders.

When managers receive complaints from staff about colleagues speaking another language, what is the appropriate first step? How can they address the issue without creating a discriminatory environment, particularly regarding personal time like lunchbreaks?

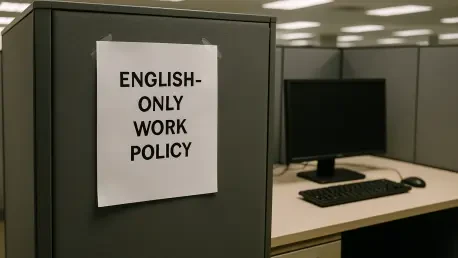

The absolute first step is to pause and investigate, not react. A manager’s immediate impulse might be to solve the perceived problem, but issuing a blanket “English only” rule is a direct path to a discrimination claim. This is exactly what happened in the recent case, where a manager, responding to complaints, told an employee not to speak Swahili and ended up causing profound humiliation. Instead, a manager needs to ask critical questions: Is the conversation work-related? Is it happening during work hours or on a personal break? A rule that bleeds into personal time, like a lunchbreak, is almost never defensible. Imagine being told you cannot speak to your family in your native language during your one break in the day; it’s incredibly isolating and, as the tribunal found, can be deeply derogatory. The correct first move is always to gather context and then immediately consult with HR before taking any action.

A company’s internal grievance investigation concluded no discrimination occurred, yet a tribunal later found the opposite. What are the common pitfalls in such internal investigations, and what practical steps can HR take to ensure a fair, impartial process that makes employees feel heard?

This is a classic and costly mistake. The biggest pitfall is when an investigation becomes a defensive maneuver to protect the company rather than a genuine search for the truth. In the case we’re discussing, the investigation concluded there was no discrimination, which only compounded the employee’s feelings of humiliation and hostility. He felt completely unsupported. To avoid this, HR must ensure the investigation is impartial, which might mean bringing in a third-party investigator if internal bias is a risk. It’s crucial to take the complaint seriously from the start, document everything meticulously, and interview all parties with an open mind. The goal isn’t just to produce a report; it’s to make the complainant feel genuinely heard and supported. When that process fails, you not only risk an £11,000 judgment like this one, but you also create a toxic culture where no one feels safe to speak up.

How can a company create a fair workplace communication policy that balances operational needs for a common language with the risk of discrimination? What specific elements should this policy include, and how should it be explained to a diverse workforce to ensure understanding and buy-in?

A fair policy is all about necessity and clarity. It’s generally reasonable to require a common language, like English, for work-related communications to ensure clarity, safety, and inclusion. The policy should explicitly state that this requirement applies to tasks, meetings, and official communications during working hours. Crucially, it must also clearly define what it doesn’t cover: personal conversations during breaks, lunch hours, or private phone calls. The rationale must be explained to everyone. Frame it as a tool for effective collaboration and safety, not as a restriction on cultural identity. When you roll it out, hold sessions to discuss it, answer questions, and emphasize that the company values the linguistic diversity of its workforce. Without that proactive explanation, a policy can feel punitive and discriminatory, regardless of its intent.

In one case, a judge noted a manager failed to realize the offensive nature of an “English only” instruction. What specific training or resources should organizations provide to line managers to improve their cultural competency and prevent discriminatory actions before they escalate?

That finding is so telling—it highlights a complete failure in management training. Managers need more than a 30-minute webinar on diversity; they need immersive, scenario-based training on cultural competency and unconscious bias. This training should cover the real-world impact of seemingly small actions, like an offhand comment about language. It needs to equip them with the skills to recognize a potentially discriminatory situation and understand their legal and ethical obligations. We need to move managers from a place of not realizing their remarks are offensive to instinctively knowing to seek advice before acting. Furthermore, they need clear resources—a direct line to HR, simple guides, and checklists—so that when they receive a complaint, their first step isn’t to issue a clumsy directive but to engage a proper, supportive process.

Sometimes a performance management program can be initiated based on a biased view that speaking a foreign language is disruptive. What are the key warning signs that unconscious bias is influencing performance reviews, and how can organizations audit their processes to ensure they are equitable?

This is a subtle but incredibly damaging form of discrimination. In the Ruiza case, the performance management program was explicitly linked to the “racist” view that his use of Swahili was disruptive. A major warning sign is when performance feedback becomes vague and subjective, using words like “disruptive,” “not a team player,” or “communication issues” without concrete, objective examples tied to job duties. Another red flag is a sudden drop in performance ratings for an employee from an underrepresented group immediately following a culture-related complaint. To combat this, organizations must audit their performance management systems. This involves analyzing review data to see if employees from certain backgrounds are consistently rated lower, scrutinizing the language used in written feedback, and implementing a calibration process where managers must defend their ratings to a group of peers and HR. This forces objectivity and makes it much harder for one person’s bias to unfairly derail someone’s career.

Do you have any advice for our readers?

My advice is to treat your workplace culture as a garden that needs constant, proactive care. Don’t wait for the weeds of discrimination to take over before you act. Invest in meaningful training for your managers, review your policies through the lens of your most vulnerable employees, and when a grievance is raised, treat it as an opportunity to listen and improve, not as a threat to be neutralized. Building an inclusive environment isn’t about perfectly avoiding mistakes; it’s about creating a system that responds with empathy, fairness, and a genuine commitment to getting it right. That’s what builds trust and protects both your employees and your organization.